West Indian Creek Winter 2024

Dates to Remember

February 9 - Forestry Day at The Front Porch

Join us 9am-3pm at The Front Porch in Kellogg for discussion on forest management, foraging, noxious weeds and more!

$12 registration includes morning refreshments and lunch

February 3 - EQIP Special Sign-up deadline for West Indian Creek. Funding available for landowners and operators in West Indian Creek. Please contact John Benjamin for details (651) 560-2050 or John.Benjamin@usda.gov

Meet Miscanthus saccariflorus aka Amur silvergrass

Have you seen this plant? Miscanthus saccariflorus, common Amur silvergrass, is an invasive grass. It can be confused with Pampas grasses, also invasive to this region. The plant forms dense monocultures that outcompete native plants and may affect wildlife habitat. Amur silvergrass mainly spreads via rhizomatous roots. Rhizome fragments that move to new locations can result in a new infestation. It is quite tolerant of wind, its flowers are wind pollinated and seeds are dispersed by wind. Amur silvergrass can be found planted as an ornamental across many areas of the United States, especially the Northeast and the Midwest. It has been known to escape plantings and invade nearby natural areas.

Its potential ability to hybridize with Chinese Silvergrass (Miscanthus sinensis) may be an issue as hybrids of these two species may be able to produce prolific amounts of seed. The plant was recently added to Minnesota Department of Agriculture's Noxious Weed Restricted List. Addressing invasives early on in their establishment is easier and less costly. Big bluestem and Indiangrass and two tall native grasses to consider for planting instead. To learn more how to control and report it please visit MDA's website: www.mda.state.mn.us/reportapest

You may contact Kayla Haberkorn, Wabasha County Weed Inspector at 651-565-3068 or khaberkorn@co.wabasha.mn.us

The Impact of Land Use Changes on Farming Profitability

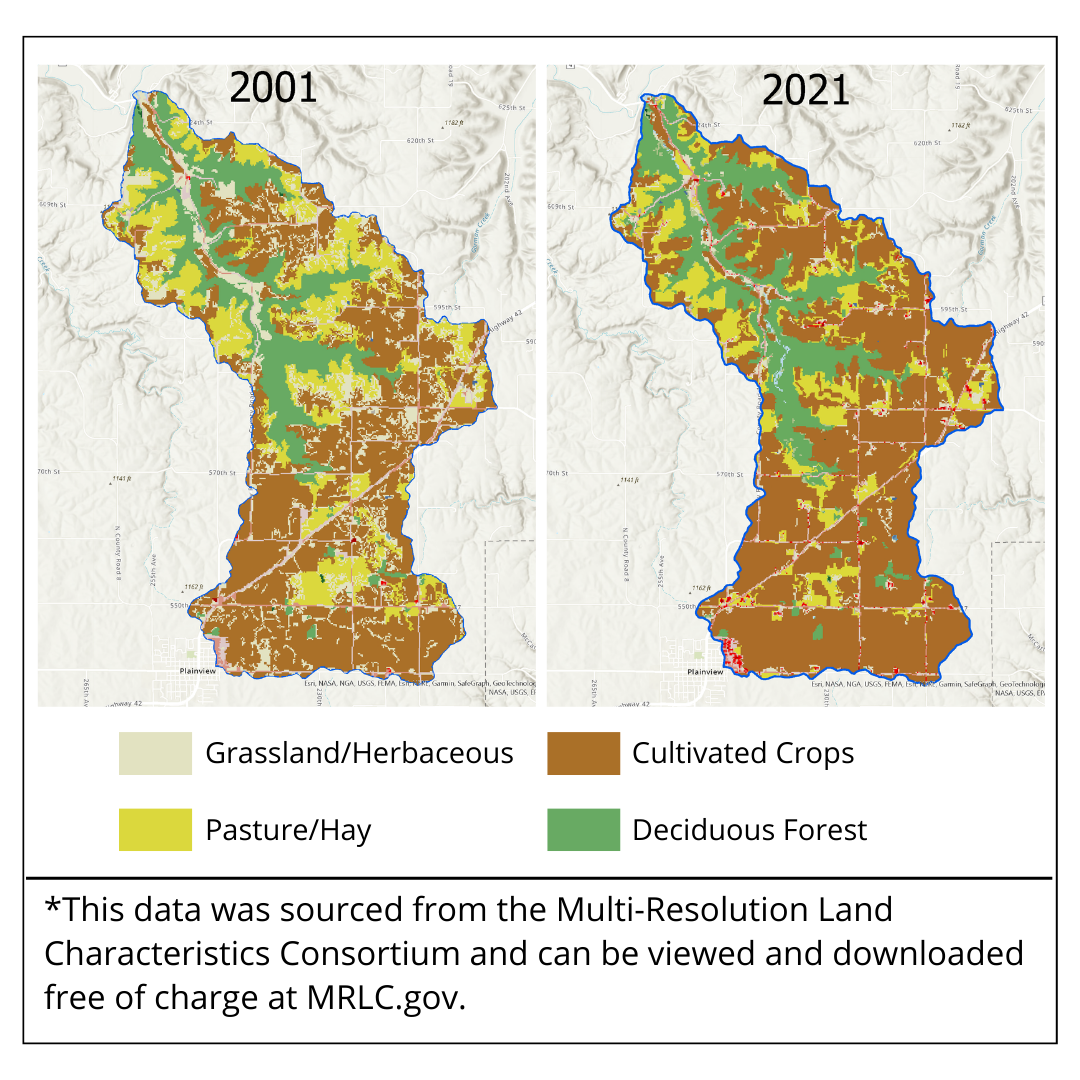

Since 2001, there has been an increase in frequency of land use change across the United States. Most of this change has been loss of forested land, urban expansion, and cultivated crop expansion according to data from the National Land Cover Database. In West Indian Creek, the greatest change has been cultivated crop expansion. Between 2001 and 2021, there was a decrease in hay and pastured acres by 4.4% and a decrease in grassland and herbaceous cover by 12.2%, while cultivated crop acres increased by 14.5% (see map) *. But what does this mean, and why does this matter?

It comes down to soil health. Soil health has been the buzzword in agriculture for several years now, and for good reason. The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) defines soil health as the “continued capacity of soil to function as a vital living ecosystem that sustains plants, animals, and humans.” Soil health is attained by maximizing presence of living roots, soil cover, and biodiversity, while minimizing soil disturbance – which is something perennial cover is great at doing. Pasture, hay, and herbaceous cover are all forms of perennial vegetation because they have living roots in the ground at all times of the year. The benefits of perennial cover include increased water infiltration, flood resiliency and decreased peak flows, carbon sequestration, habitat and biodiversity, filtering and buffering of pollutants, nutrient cycling, and improved soil structure.

Unfortunately, with the pace of land use change and increased soil disturbance, our annual soil loss has surpassed that of the Dust Bowl. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, 1.2 billion tons of soil were lost during the peak of the Dust Bowl, while the most recent update from the Natural Resources Inventory reports 1.7 million tons of soil loss on cropland in the U.S. annually. This not only has serious ecological implications but will also decrease farm productivity and profitability. Soil loss is nutrient loss. A study in the Soil Science Society of America Journal showed that eroded sediment has 2.1x more organic matter, 2.7x more nitrogen, 3.4x more available phosphorus, and 19.3x more available potassium than the bulk soil. Fertilizer expenses typically account for one-third of total input costs for crop operations, so that eroded soil is dollars washing away. Other costs of soil loss include decreased water holding capacity, resulting in increased irrigation costs and significant crop stress especially during drought years like 2023.

Managing for soil health and keeping soil in its place can help mitigate these costs and lead to increased resiliency to market changes, drought, and extreme weather. We have observed that some folks have a hesitation to adopt soil health practices because they fear the potential impact on yield. However, return on investment (ROI) is an important detail to analyze. An executive summary from Minnesota State Agricultural Centers of Excellence showed similar ROI for corn grown with no cover crop and corn grown after a cover crop in Southern MN, even with an average 10 bu/ac yield decrease on the cover cropped fields. Reducing tillage also offers decreased input costs, due to less time spent in the field and less fuel used. According to a report by the University of Illinois, a disk ripper and field cultivator tillage program can cost over $35/acre. Reducing tillage can save between $10-40/acre depending on the type of tillage implement used.

For corn/soy rotations, establishing perennial vegetation is not completely out of the picture. Every field has its less productive areas, especially along field edges or low spots. A study in England was conducted to see what would happen if those acres were taken out of production and put into wildlife habitat. They compared fields with no change to fields with up to 8% of converted wildlife habitat and found either sustained or increased yields over a 6-year period, despite the loss of cropland for habitat creation. The increased productivity per acre on in this study was attributed to the benefits of perennial cover mentioned earlier, especially increased habitat and biodiversity that allowed pollinators and beneficial insects to thrive. Now, there is a new buzzword for this practice and that is “precision conservation.” This method utilizes precision ag technology to identify underperforming acres both in crop productivity and ROI. In a webinar hosted by Iowa Learning Farms, it was shown that poorly performing acres are often revenue negative, costing the farmer more than $200/ac to farm. They also demonstrate how the technology can be used to choose conservation practices that are revenue positive. The webinar recording is available to view online at: tinyurl.com/precisionconservation

Making changes to your operation can feel intimidating, and building soil health takes time, which is why there are resources available in the form of technical assistance and/or cost share programs. Please contact the Wabasha SWCD or NRCS for questions about best management practices, programs available, or for assistance on your farm at (651) 565-4673 ext. 3.